Prairie Moon Sculpture Garden and Museum

Herman Rusch was born in 1885 to parents who had emigrated from East Prussia to Trout Run Valley near Arcadia in northwestern Wisconsin. In his teens, Rusch began working as a hired hand. Years later in 1914, he took over the family farm when he married a woman named Sophie, and together they raised three children. In his spare time he loved playing the fiddle at community events and participating in fiddling contests.

In 1952, after 40 years of working the land, Rusch retired. “To kill old-age boredom,” he first rented, then purchased the Prairie Moon Dance Pavilion and transformed it into a museum. Rusch filled the arched-roof building to the bursting point with natural phenomena, curios, unusual machines, and personal mementos. Among them were a tree grown around a scythe, a washing machine powered by a goat on a treadmill, and taxidermy specialties such as a fox and rabbit trapped in a hollow log.

Concerned that the grounds of the museum were barren, Rusch built his first concrete and stone planter circa 1958. That effort led to two new engrossing interests: the creation of huge sculptures and related flower beds. Rusch said that he “just kept on building. You don’t ever know where it will end up when you start.” Without any formal art training, he became a consummate craftsman and artist, searching local quarries for appropriate stone, and developing exceptional masonry skills.

In just one year, Rusch built a 260-foot arched fence that spans the north perimeter of the site. Its precisely aligned conical posts were constructed with alternating bands of chiseled white rocks and pie-shaped red bricks, while the arches were molded with concrete over the iron wheels of old grain drills that had been cut in half and stretched. This gracefully arched fence marked the beginning of what would become Rusch’s 16-year effort to construct a colorful fantasy world based on his belief that “beauty creates the will to live.”

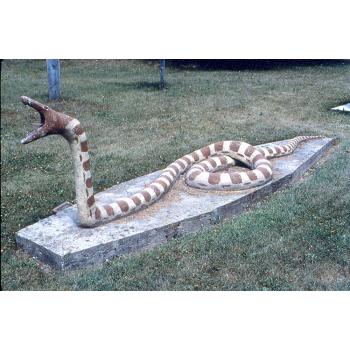

His other sculptures include a “Rocket to the Stars,” a Hindu temple, dinosaurs, even a miniature mountain. Sometimes Rusch added color to the freshly mixed concrete; sometimes he painted the surfaces. He embellished the sculptures with seashells, bits of broken bottles, and shards of crockery and mirrors.

Circa 1959, Rusch purchased four sculptures created in the 1930s by Halvor Landsverk of Minnesota, and added them to the garden. By 1974, at the age of 89, Rusch had created nearly 40 sculptures. His final piece was among his most impressive: a 13-1/2-foot watchtower, constructed with rocks he collected from a quarry high in the nearby bluffs and pieced together like a jigsaw puzzle. That same year Rusch received some attention by the art world for his work. The Walker Art Center in Minneapolis included Rusch’s art in a major exhibition, “Naives and Visionaries.”

Five years later at age 94, Rusch decided he needed a “little more time for fishing and fiddling” and sold Prairie Moon at auction, nearly dispersing the entire contents of the museum. The new owners turned the Pavilion into a dog kennel for the next thirteen years.

Rusch died eleven days after celebrating his 100th birthday in 1985, but his art remains a visual testament to his claim that, in life, “a fellow should leave a few tracks.” He also left behind a painted concrete self-portrait that gazes at his sculpture garden and commented, “I’ll still see what’s going on here when I’m not around.”

Some will remember Rusch for his curious view of the natural world made manifest in his roadside museum. Others will recall with fondness his lively fiddling at barn dances and weddings. But no one who’s seen it will forget Herman Rusch’s magnificent Prairie Moon Sculpture Garden & Museum. His powerful vision, tireless labor, and organic sense of rhythm, form, and color not only made such a feat possible, but also brought him wide acclaim.

It wasn’t until 1992 that Kohler Foundation purchased and began restoration of the site as part of its ongoing commitment to the preservation of significant art environments by self-taught artists. The conservation of sculptures required structural stabilization; surface repairs and cleaning; paint analysis including stereoscopic microscopy; and painting to re-establish the original palette. Landscaping revived the garden environment. The Pavilion was also restored with the addition of an interpretive exhibition including documentary photographs, museum artifacts, and personal keepsakes.

In late 1994, Kohler Foundation donated the Prairie Moon Sculpture Garden & Museum, an important part of Wisconsin’s cultural heritage, to the Town of Milton to be maintained as a public art site. A joyful opening celebration in 1995 brought the community and the Rusch family together with preservationists, artists, and art historians from throughout the country, an affirmation of the national significance of the art of Herman Rusch.

In 2002, a new exhibit was added to the Prairie Moon Museum. A depression era collection of miniature concrete and indigenous stone buildings modeled after actual buildings in Cochrane, Wisconsin, have been donated to the site. Created by self-taught artist Fred Schlosstein (1869-1953), the village of eighteen buildings has been carefully restored with the assistance of Kohler Foundation. The buildings had been kept in the family and were donated by the artist's grandson and his wife, Gary and Shelby Schlosstein. An outdoor installation of more Schlosstein sculptures was added in 2008.

Additional sculptures were added to the refurbished prairie area when the John and Bertha Mehringer "Fountain City Rock Garden" was moved from its river bluff hillside home to the Prairie Moon grounds. The entire site is cared for today by the Friends of Prairie Moon Sculpture Garden.

See also: Mehringer Relocated Sculpture Page

The Wisconsin Art Environment Consortium created the video podcast below about Prairie Moon:

Herman Rusch's Prairie Moon Sculpture Garden