Wisconsin Concrete Park & Rock Garden Tavern

Wisconsin Concrete Park

Born on September 20, 1886 to German immigrants who had settled in Price County in northern Wisconsin, Fred Smith was a true son of the Northwoods. When asked later in life if he had been hindered by his inability to read or write, since Smith had received no formal schooling, he replied, “Hell no. I can do things other people can’t do.” This was no exaggeration.

Like many others of his era, Smith’s education came from experience. He went into the wilderness early in life and stayed there, off and on, until his arthritic body forced him to find a more comfortable lifestyle. During the long, cold winters of his wilderness years, Smith became a logging legend. Known for his great physical strength, he eschewed the use of modern machinery and coaxed his team of horses to fell the virgin northland timber.

Despite Smith’s connection to the wilderness, he was also a family man with a 120-acre homestead. Alta B. May became his wife in 1913 and together they raised six children, born 1914-1925. During the summer months, Smith and Alta farmed their land, growing Christmas trees to sell locally, raising ginseng for the export market, and cultivating an ornamental rock garden.

In 1936, he built and operated the Rock Garden Tavern next to his home. A self-taught fiddler who made his first fiddle at age 12, Smith used the tavern as a stage to showcase his musical talent. During these early years of his life, music provided an important outlet for his boundless creativity. Later, when Smith was in his sixties, he stopped working in the logging camps and channeled his energy into another form of expression: sculpture.

Smith’s first cement piece, inspired by a picture of a large, antlered deer jumping over a log that he had first noticed on a boy’s sweater, began a 14-year obsession by one of America’s unique grassroots artists.

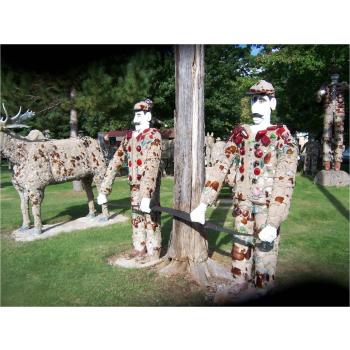

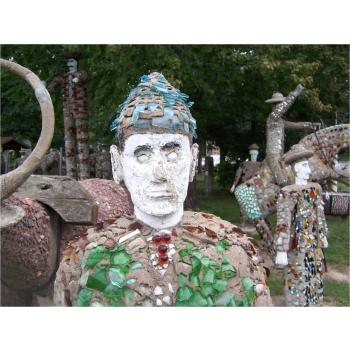

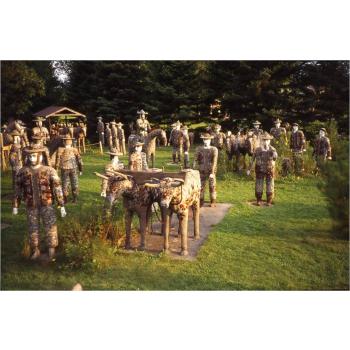

It was 1950, at age 65, that Smith began construction on his homestead farm of a fanciful yet powerful outdoor sculpture environment he named “Wisconsin Concrete Park.” Completely self-taught in his methods of construction, Smith created over 200 figures using wooden armatures wrapped in mink wire and covered with layers of hand-mixed cement. He decorated the figures with shards of broken glass and found objects. As proprietor of the Rock Garden Tavern, he had a ready supply of Rhinelander Beer bottles for his sculptures and also gladly accepted glass objects from tourists who happened by. He used everything at hand, and had an innate sense for the inherent aesthetic, and sometimes historical value contained in common objects. Smith’s embellishments deflected rain, reflected light, and enlivened the sculptures with sensational compositions of texture and color.

Because his statues were often massive, Smith built them in pieces, pouring the concrete into molds dug into the earth. Then, weather permitting, he enlisted the aid of relatives and neighbors to hoist them onto prepared footings, anchoring the statues and attaching various parts with more cement. Smith carefully sited the statues to create a cohesive panorama of history, legend, and his immense imagination. He was convinced that his work was important and that it was essential for people not only to see it, but to see it exactly where it was built. His insistence on this was underscored by his refusal to sell anything or to accept commissions, although he received several lucrative offers.

His sculptures immortalized characters not only from local legends and contemporary newsmakers, but also from personal acquaintances and mythic heroes. Grouped together on about 3.5 acres within the 16.2 acre park are recognizable figures like Ben Hur, the Lincolns, Paul Bunyan, Mabel the Milker, and Sacajawea. Other generic figures include a double wedding party, an itinerant cowboy drinking beer, and a musky pulled by horses. These figures reveal Smith’s interpretation of his Northwoods culture and of the world beyond. They are his own means of storytelling sprung from his passion to create. “It was in me,” was the explanation he offered.

He continued to work, welcoming both visitors and the increasing notoriety, until a stroke in 1964 finally halted his creative labor. He had just completed the last horse in the Budweiser Clydesdale tableau. Confined to a nursing home in 1968, Smith anxiously planned for additions to his park until his death on February 21, 1976.

Shortly after the death of Fred Smith, Kohler Foundation, Inc., purchased Wisconsin Concrete Park. In February, 1977, The Wisconsin Arts Board, the state arts agency, undertook the restoration of the Park with funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, the State of Wisconsin, and private contributions. Unfortunately, with restoration well underway, a devastating wind storm struck in July, damaging over 70% of the figures, uprooting hundreds of the tall pines planted by Smith decades earlier, and destroying Smith’s barn which was being used as a studio by the conservators. Oddly enough, the storm actually provided an opportunity for more thorough restoration. The original rotted wood armatures were replaced with steel, and various strategies were used to reassemble the pieces in an attempt to make them more impervious to extreme climatic conditions.

When restoration was completed in the fall of 1978, Kohler Foundation gifted Wisconsin Concrete Park to Price County, making the art and park area accessible to the public. It is maintained and preserved by Price County with financial and conservation support provided by the Friends of Fred Smith.

Fred Smith would delight in knowing that his work has gained the deserved reputation as one of the more exceptional and original sculptural environments in the world, drawing visitors from around the globe.

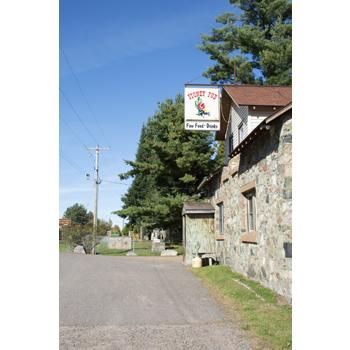

Rock Garden Tavern & Fred Smith's Portrait

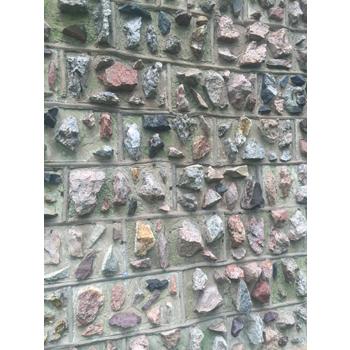

In 1936, Fred Smith built and operated the Rock Garden Tavern next to his home, which was known later as the Stoney Pub. A self-taught fiddler who made his first fiddle at age 12, Smith used the tavern as a stage to showcase his musical talent. During these early years of his life, music provided an important outlet for his boundless creativity. Later, when Smith was in his sixties, he stopped working in the logging camps and channeled his energy into another form of expression: sculpture. He, John Raskie, and Albert Raskie, an accomplished mason, built the entire exterior structure and interior decorative bar. Smith also displayed his smaller art pieces on the back bar. Smith made ingenious, homemade concrete blocks for an addition to the Tavern, using the same techniques he used to build the sculptures on his property.

KFI acquired the building in 2018 and renovated the tavern and upstairs apartment. The building was gifted to the Friends of Fred Smith which now operates the tavern, the upstairs apartment as an Airbnb that is a perfect location for visitors to the park. The funds raised from the Tavern and Airbnb helps support the Wisconsin Concrete Park ongoing maintenance of the site.

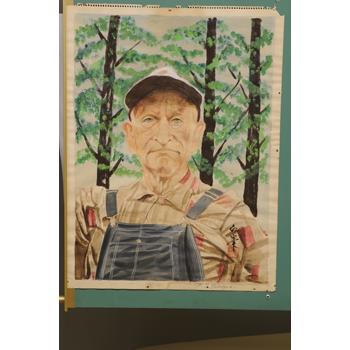

In addition to the restoration of the building, Fred Smith’s portrait was also saved. A watercolor portrait by P. T. Shinozaki has hung for decades in Phillips, Wisconsin at the Rock Garden. The painting required minor repairs to the frame and matting.The owner, Bill Elliott, gave it to KFI for gifting to the Friends of Fred Smith so it can become part of the Wisconsin Concrete Park.

For more information on Wisconsin Concrete Park visit www.friendsoffredsmith.org.

The Wisconsin Art Environment Consortium created the video podcast below about Wisconsin Concrete Park:

Fred Smith's Wisconsin Concrete Park